Guest Article: Evanescent Riders of the 1890s: The 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps

Joshua – of Beer in the Bidon fame – returns from the depths of doing something scholarly in Montana. I hadn’t realized that Montana even had schools, but apparently they have loads of them. And, based on the fact that they awarded him a Ph.D., they are apparently prone to poor judgement.

Josh deposited this little gem in the queue on his way from Montana to his new home in Portland where I expect he will resume his research on beer.

Yours in Cycling,

Frank

—

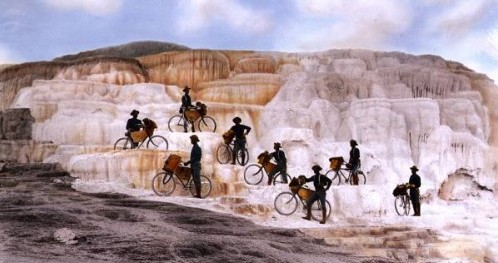

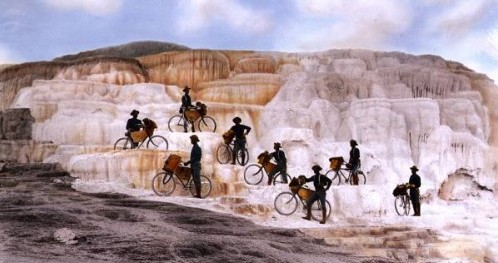

It took me a moment to recognize exactly what I was looking at. Eight men, dressed in the boots, high-waisted woolen pants, and flat-brimmed hats of 19th century U.S. Infantry. The men posed on nearby Minerva Terrace, next to elegantly simplistic steel-framed, fixed-gear machines, loaded with gear. Fit men. Strong men. Hardmen. Rouleurs. Black men?

In retrospect, had I not been blessed with a certain mastery of body and mind that makes the true cyclist feel at home in any setting, I myself might have made for an odd site, standing there staring in disbelief at an 1896 photograph of Missoula, Montana’s 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps on the wall of the Mammoth Hot Springs Lodge in Yellowstone National Park. Bleary-eyed and at the end of a hot half-century from the south end of the Hayden Valley, standing in full kit amidst a sea of cotton-clad tourists ambling out of their RVs to perv the elk grazing on the lawn, I couldn’t have been more out of place to the common observer. But I was an anomaly staring at an even greater anomaly. Sure, the rouleur, casually deliberate in posture and psyche, graces in 21st century Yellowstone only periodically… but what the fuck were eight black soldiers doing riding fully-loaded bikes around Yellowstone in 1896?

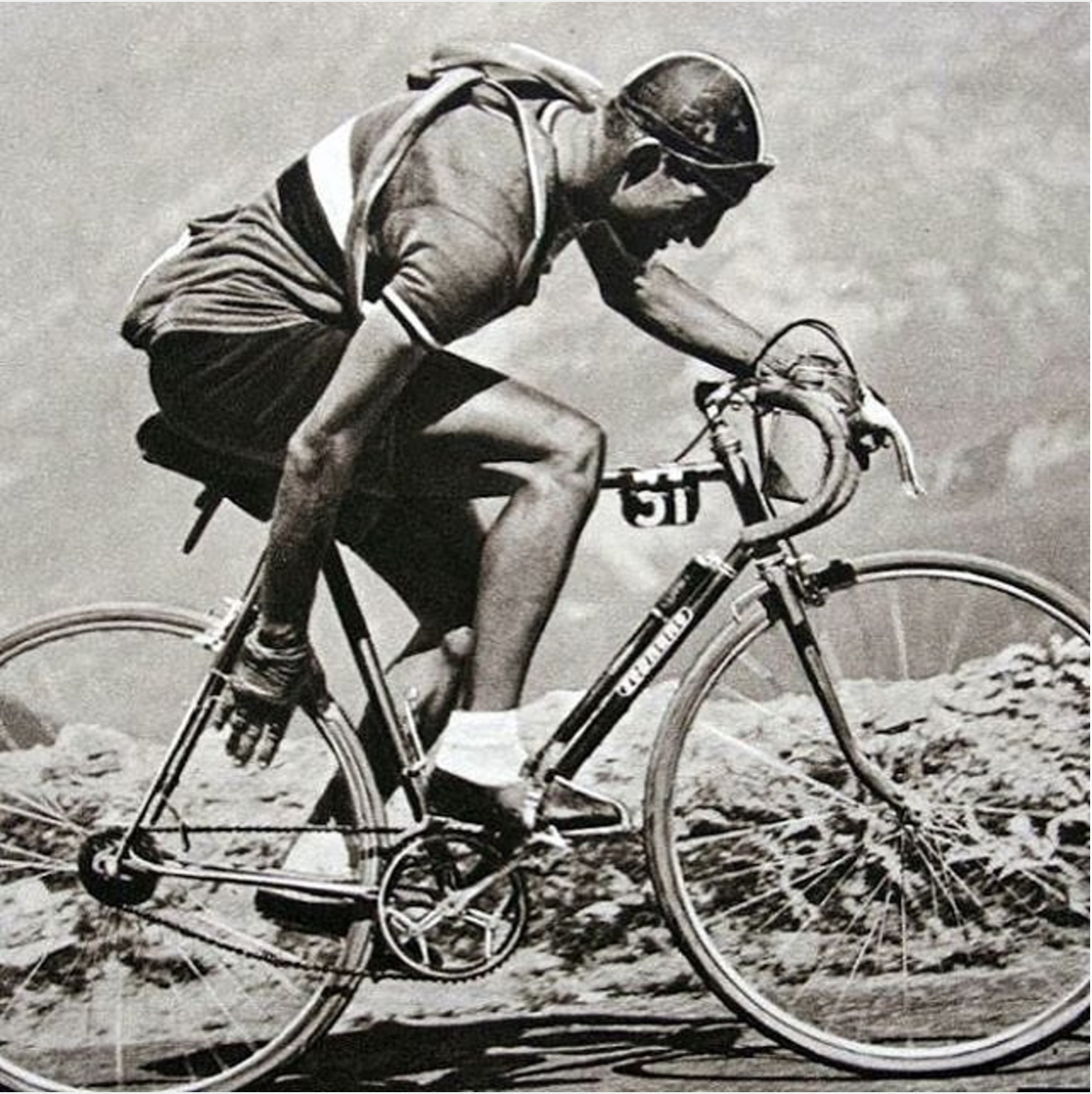

The answer, of course, is that they were following orders. And there orders were to serve up a huge helping of the V to a Western America steeped in hardmanhood but only just coming to terms with the reality of a new breed of elite pain-mongerer who had traded in leather and tack for the sleek beauty of steel and rubber.

More specifically, they were following the orders of Lt. James A. Moss, the ranking officer and progenitor of the U.S. Army’s first officially sanctioned experimental bicycle unit. Moss’s orders were simple: ride to Yellowstone. Hang out. Ride back. Thus, essentially, was the legend of the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps cemented in Montana lore.

The advent of Missoula’s Bicycle Corps and the account of its two major tours””the first to Yellowstone in 1896 and the second an epic, salt pork-fueled slog to St Louis, Missouri in the summer of 1897″”have become a familiar tale in Montana’s history.

22-years old and last in his class at West Point, Moss arrived at Fort Missoula in 1894. He found the place a little boring. The last major skirmish between Army troops and the region’s Nez Perce was more than a decade old, and the Army itself had begun to recognize that perhaps Fort Missoula had outlasted its utility. Moss and his men had little to do but drink and drill, and the young lieutenant, not yet versed in Rule #10 and Rule #47, didn’t particularly like either one.

Moss turned to something””perhaps the only thing””he was relatively good at: cycling. Having read a number of manuals on military cycling produced by European bicycle units and entrepreneurial American bicycle manufacturers eager to capture the military market, in April of 1896 the young lieutenant petitioned the Army to allow him to form a small bicycle corps to test the utility of the bicycle as a vehicle for American military use in Montana’s rugged, mountainous terrain.

The Army approved. Military brass had only one condition; the Army would not buy the bikes. In place of Army issued machines, Moss secured modified “test” versions of the “Spalding Racer” and “Spalding Special” from Chicago-based A.G. Spalding and Brothers””a venture the young Spalding Company took to with alacrity in a competitive and contracting bicycle market. By the fall of 1896, the 25th was rolling, first across Southwestern Montana and then, later, across the Eastern Rockies and the Great Plains to America’s Gateway to the West, St Louis.

The story of the 25th has fascinated its authors in the same way the photographs on the wall of the Mammoth Hot Springs Lodge so fascinated me the first time I saw them, in full kit amidst the masses, years ago. Consequently, it is a story well told. George Niels Sorensen chronicled the 25th’s exploits in his 2000 book, Iron Riders: Story of the 1890s For Missoula Buffalo Soldiers, and that same year PBS released a documentary, The Bicycle: America’s Black Army on Wheels. The Historical Museum at Fort Missoula houses a variety of historical materials on the 25th, including one of the original machines.

At first, the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps appears as a startling anomaly in our image of the historical landscape of Montana””and one incongruous with a sport whose roots and traditions are so clearly dominated by continental Europe. Black men in military garb riding bicycles across the rugged 19th century West strikes us as interesting because we can only imagine how wholly and completely out of place these soldiers and their machines must have been at the time.

But the true rouleur knows better. Yes, as the only officially sanctioned Army bicycle unit in the US””and one operating far out in a rugged new state, no less””the 25th has a unique place in history. As a Buffalo Soldier unit, its demographic makes it more remarkable still.

The American Velominatus knows that the roots of the V not only run deep but also spread wide. And in the Western United States of the 1890s, hardmen with guns (literal and figurative) on steel steeds were not out of place at all.

In fact, when the 25th rolled through the Gallatin Valley in 1896, it was almost normal. Moss and the U.S. Army came to cycling relatively late, at the back end of a nearly decade-long boom in cycling and bicycle design that supported more than 300 bicycle manufacturing firms, producing more than a million bikes in 1896 alone. Touted as the “nag of the people,” the so-called “safety bicycle”””a chain driven machine with pneumatic tires that bears a striking resemblance to something you might find between the legs of a skinny-jeaned hipster stopped to smoke an America Spirit outside of H&M””made the sport accessible as transportation and recreation across the rigid lines of race, class, and gender characteristic of Victorian culture.

Bicycles constituted a physical embodiment of a new, mechanistic age with all of its efficiency, independence, and spirit of reform. The velominata, velomihottie, and cognoscentrix flourished, their newly-trousered legs churning in silky-smooth strokes that tantalized the uninitiated and exploded the period’s stuffy gender norms.

Bicycles were wildly popular and widely used, and for a time, track racing was America’s most cherished sport””more popular even than baseball. In the same year that the 25th embarked on its first mission, the man who would eventually become America’s first cycling world champion, Marshall “Major” Taylor, himself African American, launched his professional cycling career in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Meanwhile, the 25th’s first major destination””Yellowstone””was already on the American cycling map. As David Herlihy notes in his Bicycle: The History, tourists had begun to show up en velo in the park as early as 1884.

And the American Velominatus, though he tips his stylish cycling cap toward the old countries with a casual and yet earnest respect, knows this.

The American Velominatus knows that when Moss rolled past the artist Frederic Sackrider Remington on his way up the ragged railway service road in the pie plate that was his only gear (obviously) on his way over Bozeman pass, he pointed to his crotch, gave Remington the finger for his Alsace-Lorrainian roots, and yelled out across the continent””and across the Atlantic””in the primal scream of a cycling tradition that, like the nation that birthed it, had a big toe in the sands of Calais, but a huge fucking boot in the badassedness of a huge new landscape.

And Remington, ever the gentleman, delivered the message to its intended audience–the Belgians–in simple prose. It read:

“I got yer pavé right here!”

[dmalbum path=”/velominati.com/content/Photo Galleries/[email protected]/25th Infrantry/”/]