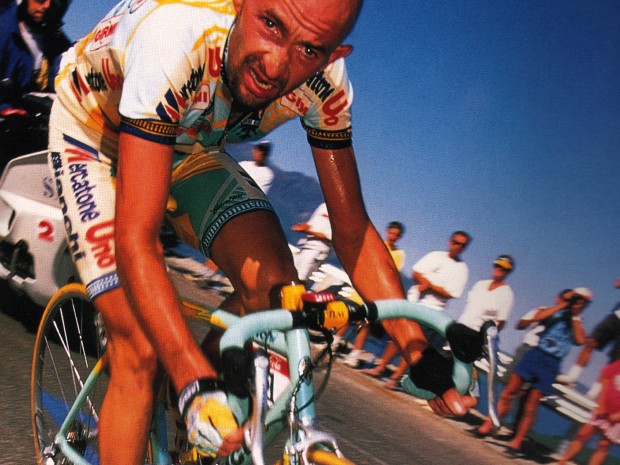

Look Pro, Part VII: Sur la Plaque, Part Deux

Our last Look Pro edition discussed moving Sur la Plaque as you approach the top of the climb, thereby reducing your riding companions to withering leaves of wet lettuce. But the article ignored the other component of climbing like a Pro, which is commonly referred to as going Steady Up with More Speed. Right from the bottom.

Many riders make the mistake of assuming that going less hard is an easier way to get up a hill than by drilling it. In fact this is a myth. Scaling a climb at speed is in many ways easier than ascending slowly. At low speeds, we stretch the duration of the climb, we feel every change in gradient, our minds dwell on nuances that might indicated how we’re feeling or how well our machine is adhering to the Principle of Silence. None of these help you climb better.

But, assuming you can sustain the effort, going faster up a climb accomplishes several things. First, rhythm is everything. You body is completely dominated by rhythm, and cycling is no exception. The beating of your heart, the rate of your breathing, the cadence being tapped out by the guns; all these things work together. Settling into your natural cadence in a higher gear means you’ll go faster. Your body wants to maintain the rhythm it’s in, so it will assist you in keeping the speed higher. As you feel your cadence lift and body start to groan, flick your chain into a cog less. Your body will again seek out the cadence it was in – at a faster speed.

Second, momentum is everything, and carries you over the changes in gradient with little effort. Hitting a steep ramp at low speed will dramatically change your rhythm and velocity. Hitting it at high speed means that lifting out of the saddle and adding just a bit more power will let you dance over the ramp with hardly a change to your effort.

Third, the duration of the effort is much shorter. This seems obvious, but consider my climb up Haleakala. It took me four and a half hours, while Ryder Hesjedal motored up that brute in two and a half. That means that at any given time, he was going a little less than twice as fast as I was. That’s a lot more speed, but the complexities of maintaing an effort and keeping the body topped up on fluids and foods are disproportionately greater for a four and half hour effort than they are for a two and a half hour effort. The simple fact is that Ryder could do it and I would have been collectedin a dustbin, but his shorter effort is easier to gauge and monitor, given that it can be sustained.

The mistake most riders make when beginning a climb is to reserve strength or recover from a previous effort by easing off prior to the accent and on the lower slopes. Worse yet is the impulse to downshift at the base into the gear you expect to do the climb in. Counter-intuitive as it may be, increase your speed as you approach the climb. Hit the base as fast as possible, and only downshift as the gradient increases in order to avoid going into the red. A trained cyclist can sustain an effort just below the red zone for quite a while; so long as you don’t go red, you should be able to sustain a high pace.

Breathing also plays a major factor. Many riders will ignore their breathing entirely and slip into short, shallow breaths that start to fall into rhythm with your cadence. Other riders will only start to control their breathing as the effort takes its toll. This is the kiss of death for your climbing. Control your breathing in long deep breaths from the base of the climb and don’t slip into short shallow ones despite the considerable temptation to do so.

In summary, take it from a guy who can’t climb for shit and keep these pointers in mind:

- Attack from the bottom and only shift as necessary. If your cadence lifts, drop the chain into a cog less, and your body will either gravitate towards lifting the tempo in order to stay in it’s rhythm, or you’ll crack entirely.

- Don’t downshift to ride over the steep bits; raise out of the saddle to power over changes in gradient.

- Breathe deep from the bottom, loading your blood up with oxygen. Don’t let your competition see or hear your breathing, though, so do this stealthily.

- An unzipped jersey flapping in the wind not only looks Pro, but helps free up your abdomen for better breathing. Be careful on this one, though – unzipping for a short climb just makes you look like a tryhard wanker. Also make sure to zip back up in full casually deliberate style at the top.

- Cracking completely and pedaling squares after a failed effort looks very Pro, surprisingly enough. Don’t be afraid to overshoot your limit and crack; you might just make it before blowing up.