Defining Moments: My First Kit

As children, none of us were given an allowance. Instead, we were taught from a young age that if we wanted to buy something, we had to earn the money in order to do so. To facilitate the model, and possibly to avoid child-labor law infringement, we were paid to do chores around the house in exchange for a cash payment directly proportional but not necessarily related to the amount of time it took us to execute the task. The hourly wage, at it turned out, was at the discretion of the one doing the overseeing and commissioning of the task at hand.

In my view, it worked out very well for us. Coming from a family that was neither wealthy nor poor, it taught us a number of important lessons about life, money, and the important ways the two are separated. It’s one of the fundamental things I’m very glad about regarding my upbringing.

My grandmother, by choice or otherwise, was in on this scheme of leveraging our desire to earn money as a means to achieve her end of having her dog tended to regularly. As grandmothers are wont to do, however, she found ways to be knowingly complicit in circumventing the intended lesson by overpaying us for our labor; she was perhaps too fond of her dog, and I was perhaps too willing to walk it repeatedly and unnecessarily in order to earn my wage.

I don’t remember how old I was, but I was still riding my old Raleigh made of Reynolds 531 tubing and clad in a Weinmann grouppo which I now wish I’d kept; I could have been no more than 10 years old. Nevertheless, I had already made the determination, by studying the pros in the races I watched on scratchy old VHS cassettes, that if I was going to amount to any kind of cyclist, I would require proper cycling kit.

I needed cycling shorts and I needed a cycling jersey; t-shirts and an old pair of lederhosen simply wouldn’t fit the bill. And cycling shorts and cycling jerseys would cost serious money. So off I was, walking my grandmother’s dog fourteen times a day – collecting payment every time – and before very long, I had saved up the money I needed.

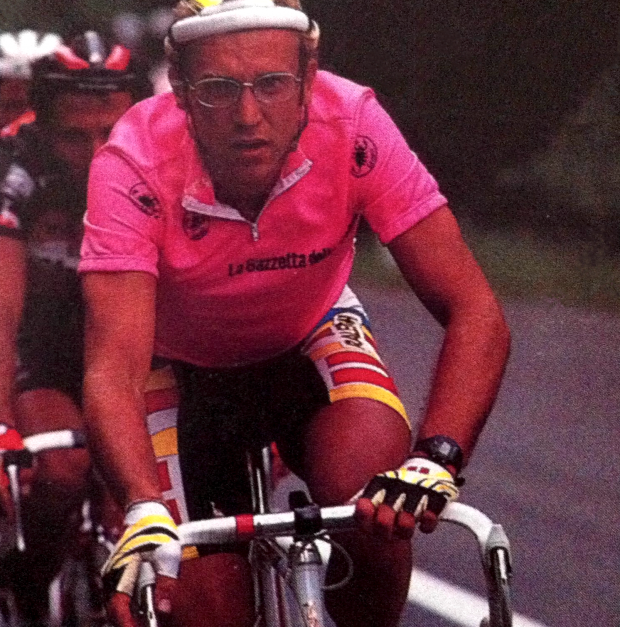

I don’t remember the name of the shop, but I do remember on which rack and in which corner of the store it hung. It resembled Laurent Fignon’s System U kit, though I felt a tinge of guilt that it wasn’t as fluorescent as LeMond’s ADR strip. It was nothing compared, however, to the unexpressed guilt I’d felt all year at secretly having hoped Fignon would win the Tour against my countryman.

Riding my trusty Raleigh, I spent the summer of 1989 riding with my left hand on the tops of my handlebars and my right hand on the hoods. I’d spotted a photo in Winning Magazine wherein Laurent Fignon was leading the Giro d’Italia riding in just this position; I summarily emulated him in this regard.

The fact that this was just a moment captured in time as Fignon changed hand position was lost on me; the fact held neither relevance nor value to my view of the world. Fignon rode like this, and so would I. This single photo fueled my desire to ride a bicycle for an entire summer. Up and down the streets I went, imagining myself making history as I left both Fignon and LeMond in my dust and I took off up the road – one hand on the tops, one on the hoods – with Phil Liggett’s voice in my ears as he commended the ferocity of my attacks.

I found daily motivation in riding like Fignon. In rain, in shine; I rode the way the photo I saw showed him riding. Every time I climbed aboard my bike, I wanted to be a better cyclist; I wanted to be more like Fignon. I was nevertheless bound to eventually discover that Fignon didn’t really ride like that; it had been a trick of the camera. By the time I discovered the truth of that photo, I had ridden like that for so long that it felt lop-sided to go back to riding sensibly, with both hands level.

I felt awkward then, riding with both hands in the drops, as I chased my sister down a mountain during a family vacation in New York State. She was in front on her Raleigh with pink handlebars, and I was frantic at the notion that she was ahead of me. There was no alternative but to beat her through the series of sharp corners coming up ahead on the road we had dubbed “Alpe d’Huez” for its steepness and numerous twists and turns.

There was, of course, a very real alternative to beating her through those corners.

As I laid in the emergency room with the doctor scrubbing furiously at my wounds, he posed several theories that might explain the flawed decision tree that placed me in his care. The prominent thought suffocating my mind was that my cherished kit had been torn apart firstly by the crash and secondly by the doctor – and that neither seemed to hold the garments in the same esteem I did. It was destroyed; a summer of over-paid dog-walking lost.

As a matter of comparison, this commercial, aired during this year’s Tour de France, is exactly how I rode as a kid. In fact, I still do today.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1BwnuBVUBsQ[/youtube]